Screen Time Isn't the Problem—Your Attention Span Is

Last year, I reduced my screen time by 40%. The numbers were clear: daily average dropped from 5.5 hours to about 3.3 hours. I felt virtuous.

But here's what didn't change: my ability to focus on demanding work. I still struggled to sustain attention for more than 15-20 minutes. I still felt the pull toward distraction, even when there was nothing to be distracted by.

Reducing screen time made me feel better about my habits. It didn't actually improve my concentration.

This experience led me to a conclusion that felt almost heretical: screen time is the wrong metric. It's measuring a symptom while ignoring the underlying condition.

The Screen Time Obsession

We've become obsessed with screen time as a measure of digital wellness. Apple and Android built tracking into their operating systems. Apps promise to help you reduce your hours. Parents worry about children's screen time numbers.

The implicit assumption is that screens are the problem, and less screen time is the solution.

But this framing is incomplete at best.

Screen time doesn't distinguish between activities. An hour reading a thoughtful article, an hour doing research for work, and an hour mindlessly scrolling—all count the same. They're not the same.

Screen time doesn't measure attention quality. You can have low screen time and terrible focus. You can have moderate screen time and excellent focus. The correlation is weaker than the discourse suggests.

Screen time reduction doesn't build capacity. If your ability to sustain attention has degraded, reducing screens creates an absence, not a skill. You're not training anything—you're just avoiding something.

What's Actually Happening

The real issue isn't time on screens. It's what constant connectivity has done to our attention capacity.

When you're accustomed to checking your phone every few minutes, your brain adapts to expect interruption. It becomes skilled at task-switching and novelty-seeking. It becomes less skilled at sustained focus on a single thing.

This is a training effect. Your brain got good at what you practiced.

The problem with reducing screen time without attention training is that you haven't actually rebuilt the capacity you lost. You've just removed one source of distraction. The underlying distractibility remains.

I experienced this directly. With my phone in another room, I'd still find myself drifting—thinking about what I might be missing, getting up to make coffee, reorganizing my desk. The phone wasn't there, but the pattern was.

The Better Question

Instead of "how do I reduce screen time?" the better question is "how do I increase my attention capacity?"

These aren't the same thing. You can reduce screen time without improving attention. You can improve attention without dramatically reducing screen time.

The screen time framing puts the emphasis on avoidance. The attention framing puts the emphasis on building.

Here's what this looks like practically:

Screen time approach: Block apps, hide your phone, track hours, feel guilty when numbers go up.

Attention approach: Train your ability to sustain focus, notice when attention breaks, build capacity progressively, use screens intentionally.

The second approach includes the useful parts of the first (reducing mindless scrolling) while adding what's actually missing (the ability to concentrate when you want to).

What Changed When I Shifted Focus

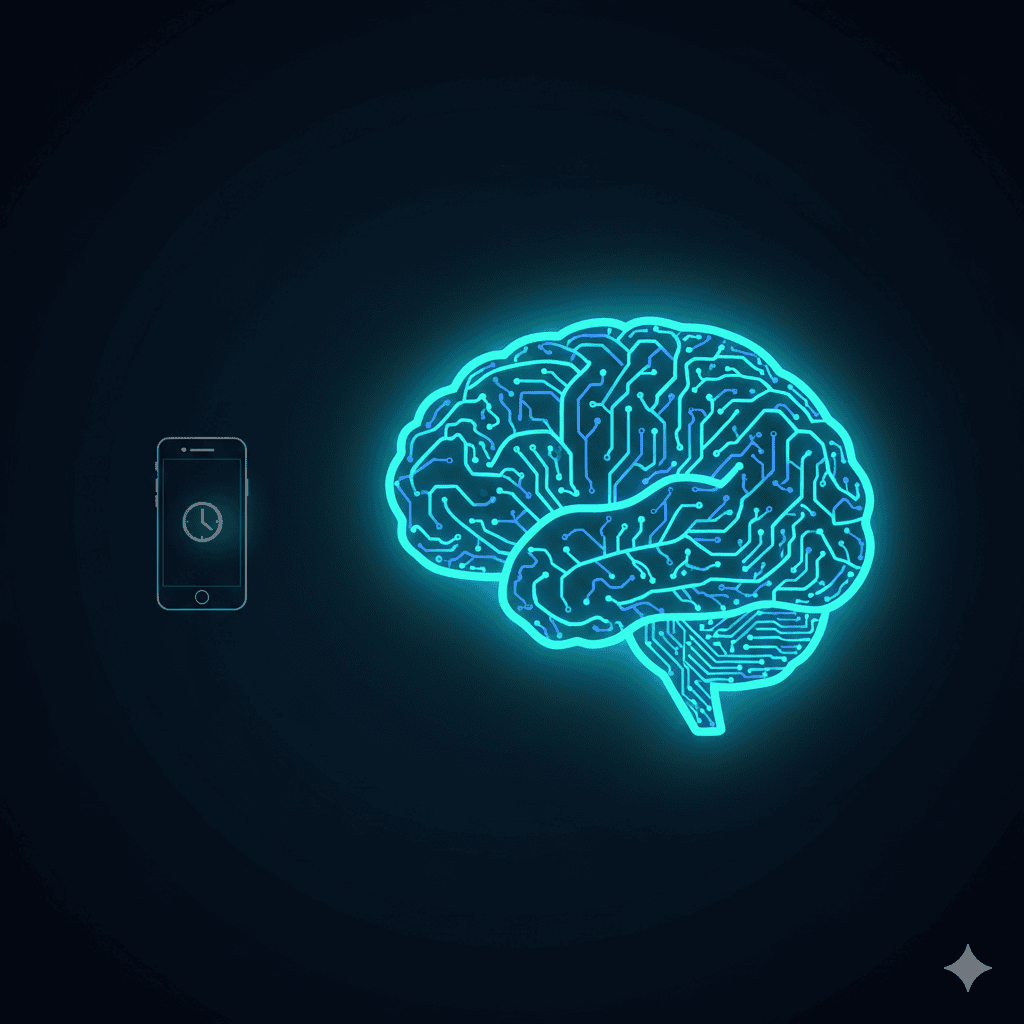

After my screen time reduction failed to improve my concentration, I tried a different approach. I stopped tracking screen hours and started tracking focus sessions.

The metric I cared about wasn't how many hours I spent on my phone. It was how many minutes I could sustain genuine attention on demanding work.

I started with 15-minute sessions—roughly my actual capacity. Over months, this increased. Not because I was avoiding screens, but because I was practicing sustained attention.

The interesting part: my screen time naturally decreased as a side effect. When you can focus for longer stretches, you don't need as many distraction breaks. When you're not fighting constant urges, you don't reach for your phone as reflexively.

But the screen time reduction was the result, not the cause, of improved attention.

We think: reduce screen time → better attention. Reality: train attention → naturally less compulsive screen use.

The Uncomfortable Implication

If attention capacity is the real issue, reducing screen time is the easy path, not the effective one.

It's easy to set app limits and feel like you're making progress. It's harder to actually train your attention—to sit with the discomfort of focus, to notice when your mind wanders, to build capacity gradually over weeks and months.

The screen time approach is appealing because it's measurable, simple, and feels like action. The attention approach is harder because it requires genuine effort and patience.

But the second approach actually works.

Something to Test This Claim

If you're skeptical—and you should be—here's an experiment:

For two weeks, stop tracking screen time entirely. Instead, track how many minutes per day you spend in genuine, sustained focus on something demanding.

Not time at your desk. Not time with apps blocked. Actual focus—attention on one thing without breaking.

At the end of two weeks, you'll have a clearer picture of what your real capacity is. You might discover that even with excellent screen time numbers, your focus capacity is poor. Or you might find that your attention is better than you thought, and the phone isn't actually the problem.

Either way, you'll be measuring what actually matters.

Where Screen Time Limits Do Help

I'm not saying screen time tracking is useless. It helps with:

- Awareness: Knowing you spend 6 hours on your phone is useful information.

- Specific compulsions: If one particular app is a problem, limiting it makes sense.

- Boundaries: Deciding not to use devices after 9pm is a reasonable boundary.

What it doesn't help with is building the capacity to focus when you need to. For that, you need to actually train focus—not just avoid screens.

The Real Goal

The goal isn't to minimize screen time. The goal is to be able to sustain attention when you want to, and to choose your screen use intentionally rather than compulsively.

These are different goals, and they require different approaches.

If you reduce screen time but can't focus for more than 15 minutes, you've solved the wrong problem. If you train attention capacity, screen time often takes care of itself—because you're no longer driven by the constant need to check something.

The screen isn't the enemy. Untrained attention is.

This is an opinion piece based on personal experience and observation. It's not a dismissal of screen time concerns, especially for children or in cases of genuine addiction. But for most adults trying to focus better, attention training is probably more valuable than screen time tracking.

Ready to rebuild your focus?

Start your 14-day free trial of FocusFit and train your attention with AI-powered coaching.

Download FocusFit