Pomodoro Timer vs. Focus Training: Which Actually Improves Concentration?

For two years, I was a devoted Pomodoro user. Red tomato timer app on my phone. 25-minute sessions. 5-minute breaks. The whole system.

It helped me structure my day. It gave me a way to track how much "focused work" I was doing. It made me feel productive.

But here's what I realized eventually: after two years of Pomodoro, my actual ability to concentrate hadn't improved at all. I was still the same person with the same distractible brain—I just had a timer running while I struggled.

That realization changed how I think about focus tools entirely.

What Pomodoro Actually Does

The Pomodoro Technique is a time management system. It chunks work into intervals, creates artificial deadlines, and enforces breaks. For many people, this structure is helpful.

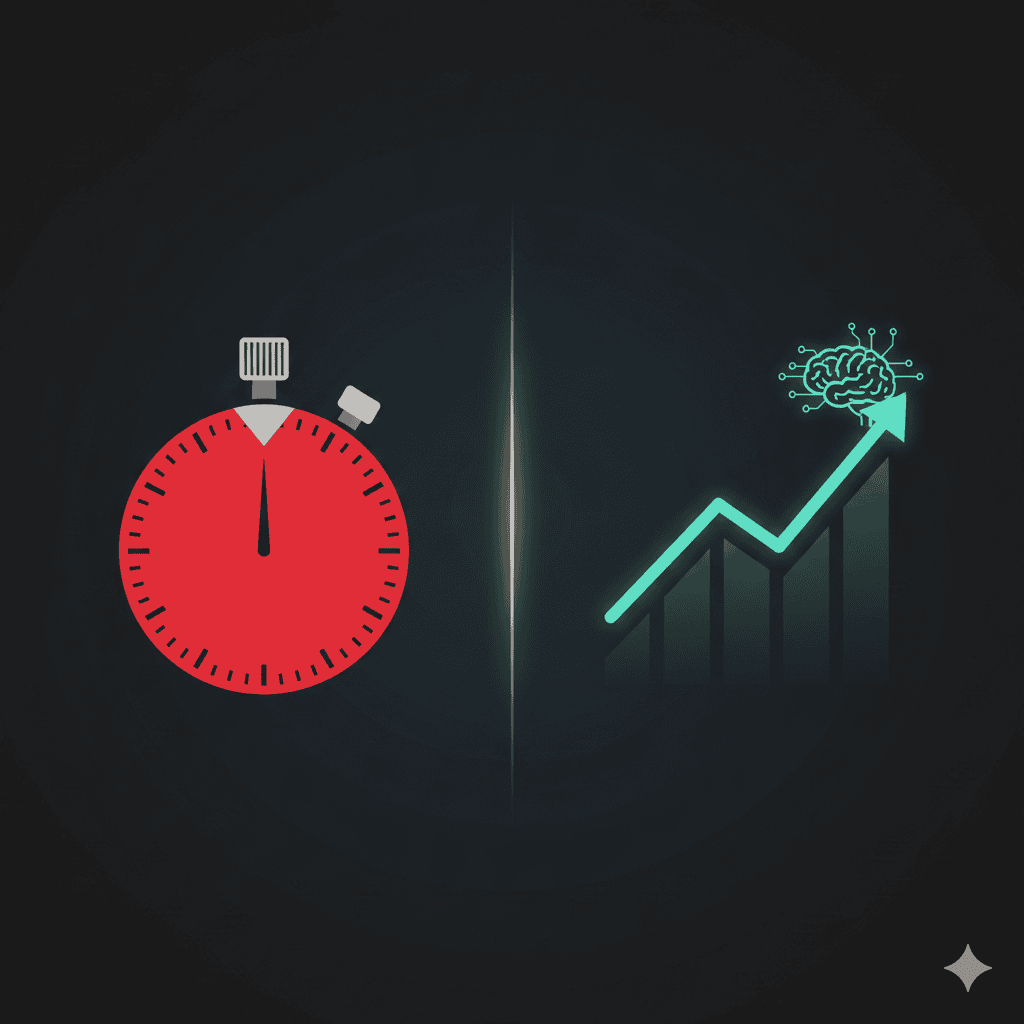

But time management and attention training are different things.

Time management asks: how do I organize my hours?

Attention training asks: how do I increase my capacity to sustain focus?

Pomodoro answers the first question. It doesn't address the second.

If your natural focus capacity is 8 minutes, running a 25-minute timer doesn't magically extend it to 25 minutes. You just spend 17 minutes fighting distraction within each session. The timer creates pressure, not capability.

I know because I tracked this. During my Pomodoro sessions, I'd often check my phone around minute 8-10. The timer kept running, but my attention had already broken. I'd pull it back, lose it again, pull it back. The session would end, I'd mark it "complete," but the quality of focus was poor.

Where the Technique Falls Short

The core assumption of Pomodoro is that focus is primarily a scheduling problem. Block the time, take the breaks, and focus will happen.

This works if you already have solid attention capacity and just need structure. It doesn't work if your attention capacity has degraded to the point where 25 minutes feels like an eternity.

Problem 1: Fixed intervals ignore individual capacity.

25 minutes is arbitrary. It was chosen because it worked for one person in the 1980s. Your optimal interval might be 15 minutes, or 40 minutes, or it might vary depending on the task, your sleep, your stress level.

Pomodoro doesn't adapt. You adapt to it—or you don't.

Problem 2: No progression system.

After a year of Pomodoro, you're still doing 25-minute sessions. There's no built-in mechanism for increasing difficulty, extending duration, or building capacity over time.

Compare this to any other skill training: running, weightlifting, learning an instrument. In each case, you progressively increase challenge as you improve. Pomodoro keeps you at the same level indefinitely.

Problem 3: It tracks time, not quality.

I could complete eight Pomodoro sessions in a day and feel like I'd worked hard. But if I'd lost focus multiple times within each session, the actual deep work might have been two hours across those eight sessions.

The timer can't tell the difference. So you optimize for completed sessions rather than sustained attention.

What Changed When I Tried Focus Training

The shift happened when I stopped asking "how do I fit focus into time blocks?" and started asking "how do I actually get better at focusing?"

This meant starting with sessions I could actually complete without breaking. For me, that was around 12 minutes. Embarrassingly short for someone who considered himself a knowledge worker.

But completing a 12-minute session—truly completing it, with sustained attention throughout—felt different than grinding through a 25-minute session with multiple attention breaks. One was an accomplishment. The other was a struggle I survived.

Over weeks, 12 minutes became 15. Then 20. Not because I forced longer sessions, but because the capacity genuinely increased. The urge to check my phone still appeared, but the automatic response to it weakened.

Pomodoro asks you to maintain focus for 25 minutes. Focus training asks what you can actually maintain, then builds from there. One is a demand. The other is a progression.

Side-by-Side Comparison

Here's how I'd compare the two approaches based on my experience:

| Aspect | Pomodoro | Focus Training |

|---|---|---|

| Starting point | Fixed 25 minutes | Your actual capacity |

| Progression | None built-in | Gradual increase |

| Success metric | Sessions completed | Attention sustained |

| Adaptation | You adapt to it | It adapts to you |

| After 6 months | Same 25-minute sessions | Measurably longer focus |

When Pomodoro Still Makes Sense

I'm not saying Pomodoro is useless. It's genuinely helpful for:

- Task batching: When you need to work through a list of small tasks

- Getting started: When you're procrastinating and need any structure to begin

- External accountability: When you want to tell someone "I'll work for 4 Pomodoros today"

If your problem is motivation or task organization rather than attention capacity, Pomodoro might be exactly what you need.

But if your problem is that you can't sustain focus—if your attention breaks involuntarily, repeatedly, even when you want to concentrate—then Pomodoro is treating the wrong problem. You don't need a timer. You need training.

Something to Try

If you're currently using Pomodoro but feeling like it's not improving your actual focus, try this experiment:

For one week, instead of 25-minute sessions, set a timer for a length that feels almost too easy. Maybe 15 minutes. Maybe 10.

Your goal isn't to complete the session. Your goal is to complete it without your attention breaking—without the urge to check something, switch tasks, or drift.

If you can do that consistently, increase by 2-3 minutes the following week.

This feels slower than just pushing through 25-minute sessions. It is slower in the short term. But you're building capacity instead of just measuring time.

The Honest Answer

So which is better—Pomodoro or focus training?

It depends on what you're trying to solve.

If you need structure and your attention is basically fine, Pomodoro is simple and effective.

If you feel like your ability to concentrate has genuinely degraded—if focus feels harder than it used to—then a timer alone won't fix that. You need something that actually rebuilds the capacity, not just tracks the time.

I wish I'd understood this distinction earlier. I spent two years timing my focus when I should have been training it.

This reflects personal experience with both approaches. Your results may vary. If you find a hybrid approach that works better, that's probably the right answer for you.

Ready to rebuild your focus?

Start your 14-day free trial of FocusFit and train your attention with AI-powered coaching.

Download FocusFit